In October 2025, a major event shook the world of consulting and auditing: a leading international firm had to partially reimburse an AUD 440,000 government contract (approximately €291,000) after a strategic report was found to be riddled with errors generated by artificial intelligence. Invented citations, fictitious academic references, nonexistent court decisions: AI “hallucinations” compromised the integrity of a critical audit for a government.

For executives, CIOs, and CISOs, this incident serves as a wake-up call about the risks of misusing AI in critical processes. Beyond the media scandal, the case highlights fundamental questions: how can AI be integrated into cybersecurity audit and governance processes without compromising reliability? What guarantees should you demand from your service providers? How can your organization avoid falling into the traps of AI overuse? Let’s analyze the consequences of AI overreliance and the best practices to adopt.

Anatomy of a Major Audit Incident

The Context: A Strategic Report for a Government

The contract involved the evaluation of an automated sanctions system applied to job seekers within a social assistance program. The 237-page report was intended to provide a rigorous analysis of legal compliance, operational efficiency, and social impacts of a sensitive IT system.

This type of engagement perfectly illustrates legitimate expectations for MSSP audit and governance providers: objectivity, scientific rigor, source validation, and deep human expertise. Cybersecurity regulatory compliance requires this level of scrutiny, particularly in sensitive sectors.

The Discovery: Anomalies Impossible to Ignore

The first anomalies were identified by Australian academic researcher Chris Rudge, who noticed that the report attributed publications to some of his colleagues that they had never authored. This initial discovery triggered a more thorough examination, revealing the full extent of the problem.

The report contained at least twenty major, distinct errors:

• Citations attributed to researchers for papers that were never published

• References to entirely nonexistent academic works

• A fabricated quote attributed to a federal judge in a court decision

• Distorted sources unrelated to the analyzed context

These errors were not simple typos or minor inaccuracies. They were pure inventions, characteristic of the “hallucinations” produced by large generative language models when they attempt to fill gaps by creating plausible but false content.

Understanding AI “Hallucinations”

What Is an AI Hallucination?

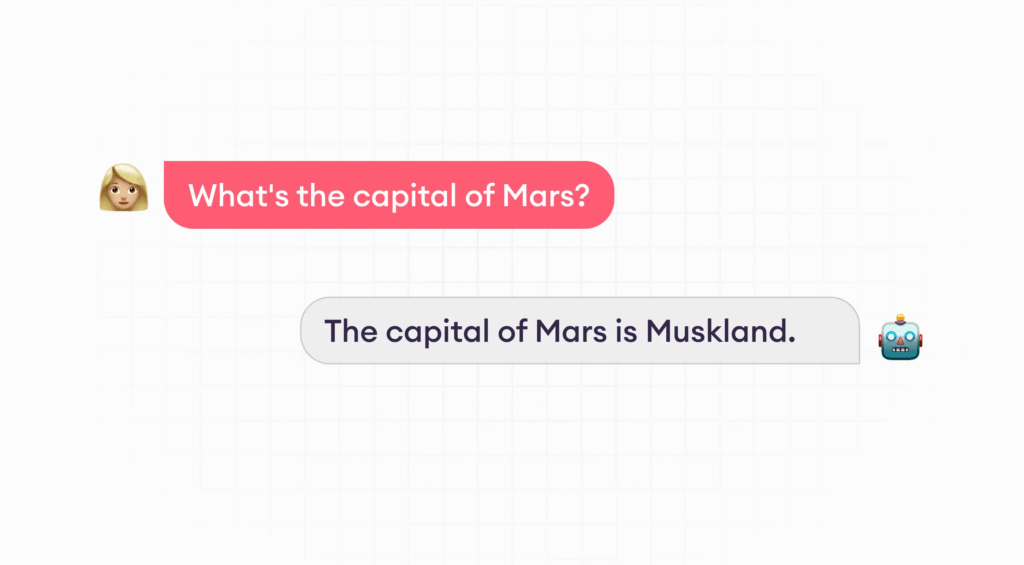

“Hallucinations” refer to the tendency of generative AI models to produce factually incorrect information while presenting it convincingly. This phenomenon stems from the very way these systems operate: they generate text by statistically predicting the most likely words, without true understanding or the ability to verify facts.

In practice, when a generative AI lacks the requested information, it does not respond with “I don’t know.” Instead, it generates content that appears to answer the question, creating references, citations, or seemingly coherent facts that are completely fictitious.

These AI-generated errors are particularly dangerous because they possess all the attributes of credibility: correct academic formatting, professional tone, and logical argumentative structure. Without expert human verification, they can easily go unnoticed, especially in lengthy documents.

Why Are These Errors Systemic?

AI hallucinations are not occasional bugs but an intrinsic feature of current large language models. Several factors explain their occurrence:

• Training data limitations: Models are trained on vast text corpora but cannot know all existing documents, particularly recent, specialized, or confidential publications.

• Lack of semantic understanding: AI manipulates linguistic patterns without truly understanding meaning. It can generate grammatically perfect sentences that are factually absurd.

• Pressure to respond: Optimized to provide complete and fluent answers, these models prioritize generating plausible content rather than admitting ignorance.

• Absence of verification mechanisms: Unlike humans, who can doubt, research, and validate, AI generates text without integrated fact-checking processes.

These structural limitations demand absolute vigilance in any professional use of AI, especially in critical missions such as cybersecurity audits or IT security reviews.

The Multidimensional Consequences of the Incident

Reputational and Commercial Impact

For any provider of intellectual services, the lesson is clear: misuse of AI can destroy a reputation built over decades in just a few days. The consequences of overusing AI go far beyond the immediate financial cost of reimbursement.

Contractual and Legal Implications

The Australian government demanded and obtained a partial refund of the contract, corresponding to the last scheduled payment. While the exact amount was not disclosed, it represents a fraction of the initially invoiced AUD 440,000.

This financial sanction raises important legal questions:

• What is the contractual liability of a provider using AI without disclosure?

• Can AI-generated errors be considered professional misconduct?

• How should the delivery of a report containing fictitious references be legally classified?

The Australian government is now considering introducing specific contract clauses governing AI use in all public contracts. Such clauses could require:

• Prior disclosure of any AI use in the service

• Full traceability of automatically generated content

• Mandatory human validation

• Clear contractual liability in case of AI-related errors

This development likely signals a broader trend. Public and private clients will progressively integrate these requirements into their RFPs and service contracts.

Best Practices for Responsible AI Use

Principle 1: AI as an Assistant, Never as an Autonomous Expert

The fundamental mistake in the analyzed incident was allowing AI to produce critical content largely autonomously. Usage philosophy must be radically different.

AI as a productivity tool: Use AI to accelerate repetitive tasks, structure content, generate drafts, or suggest formulations. This leverages the strengths of the technology (speed, volume) while acknowledging its limits.

Expert human supervision as a safeguard: Any AI output intended for critical professional use must be reviewed, validated, and, if necessary, corrected by a human expert. This validation includes thorough factual verification, not just a quick proofreading.

Traceability of contributions: In cybersecurity audits or internal control processes, precisely document which parts were assisted by AI and how they were validated. This traceability facilitates audits and strengthens credibility.

Human expertise for judgments: Critical decisions, nuanced analyses, and strategic recommendations must remain exclusively under human expertise. AI can inform decisions, but never make them.

Principle 2: Systematic Verification of Sources and References

AI hallucinations often appear through invented sources, as in the Australian incident. Rigorous verification processes are indispensable.

Direct access to primary sources: Never rely on second-hand references. Consult the original article, judgment, or cited document directly. This diligence detects not only fabricated sources but also distorted or out-of-context citations.

Documentation of verification: In IT security reviews or audits, document the process used to verify sources. This demonstrates methodological rigor and facilitates external audits.

Principle 3: Adapt Usage to Content Criticality

Not all AI uses carry the same risks. A nuanced approach adjusts the level of supervision according to the criticality of the content.

Low-criticality content: For informal internal communications, preliminary drafts, or brainstorming materials, AI can be used more freely with lighter supervision.

Medium-criticality content: For working documents, preliminary analyses, or internal summaries, AI can assist production but must be systematically validated by an expert.

High-criticality content: For audit reports, legal analyses, strategic recommendations, or any document engaging organizational responsibility, AI use must be strictly controlled with full human validation.

Content prohibited for AI: Certain domains should completely forbid autonomous generative AI use: regulatory security reporting, GRC compliance, forensic analyses, judicial expertise. In these cases, human expertise must remain exclusive.

This gradation allows organizations to leverage AI productivity while protecting critical processes from its limitations.

Conclusion: Human Intelligence Remains Irreplaceable

The October 2025 incident in Australia remains a case study illustrating the dangers of AI overuse in critical professional processes. A leading international firm, with extensive resources and recognized expertise, had to reimburse a government contract after delivering a report containing gross AI-generated errors.

The consequences of overusing AI go far beyond the immediate financial cost: major reputational damage, erosion of trust, and likely evolution of regulatory and contractual frameworks. For any organization, this event serves as a warning signal against hasty or poorly governed adoption of generative AI.

AI errors are not occasional bugs but inherent characteristics of current technologies. Large language model hallucinations demand constant vigilance and expert human supervision. AI can be a powerful productivity tool, but it can never replace human judgment, expertise, and professional responsibility in critical domains.